|

Octavia E. Butler’s novels share with readers

her extraordinary vision of what it means to be "other,"

based on biological speculation. Her Xenogenesis trilogy,

retitled Lilith’s Brood, creates

a stunning vision of abduction and seduction by an alien

species. This vision is presented in terms remarkably

consistent with molecular biology, even predicting

developments that have occurred since the novels were

written.

As the trilogy’s first book, Dawn, opens,

the human race has nearly destroyed itself by nuclear

war--"humanicide," as Butler calls it--a fate that

seemed all too plausible in the eighties, when the book

was written, and that remains a distinct possibility if

the effects of humanity on our environment are not

reversed. The few humans who survive the war are rescued

and captured by the Oankali, a nomadic alien species

that travels through the universe seeking partner

species with whom to "trade" their own genes. The story

is told from the viewpoint of Lilith Iyapo, a human

woman whom the Oankali adopt into their family and try

to enlist in recruiting other humans. Lilith is torn

between accepting the medical enhancements and the

sexual advances of her captors while trying to help

other humans escape.

Unlike the vast majority of alien abduction

tales, Dawn actually

presents a biologically plausible explanation for why

the Oankali need to interbreed with humans--despite

their own abhorrence for the human race, which to them

appears monstrous for its combination of high

intelligence and self-destructive violence, the "human

contradiction." The Oankali have evolved specialized

organs and subcellular structures which manipulate their

own genes to maximize fitness in their environment, a

self-sustaining starship which is itself a living

organism. Paradoxically, because the Oankali are such

successful genetic engineers, they tend to engineer

themselves into an evolutionary dead end; losing all

genetic diversity, they lose the ability to adapt to

change. The only way they can recover genetic diversity

is to interbreed with an entirely new species, which

contributes new genetic strengths--and weaknesses.

Butle's story evokes the experience of an

African woman swept into slavery in the eighteenth

century. Lilith’s "Awakening" among the Oankali evokes

the dehumanization of enslavement--she is naked, has to

beg for clothing, and is denied reading materials and

other access to her own culture and history. The theme

of slavery appears frequently in Butler’s books, most

notably Kindred, in which a

Black woman travels back through time to rescue a white

man who becomes her ancestor. The heroine of Kindred struggles

with the fact that she owes her own existence as an

individual to the oppressive cultural system in which

Black women could bear children only by submitting to

the advances of their white enslavers. In a remarkable

update, today's descendants of enslaver and enslaved can

use DNA analysis to go back and confront their

Jeffersonian ancestors.

In Dawn, Lilith faces

the choice of "trading" with the Oankali to produce

half-human children, or having no family at all. Like

the slaves who bore their enslavers’ children, Lilith

obtains privileges of enhanced health and security for

herself and her future children, who will be genetically

half Oankali. The Oankali lecture her about the

superiority of their egalitarian, nonviolent lifestyle,

as opposed to the hierarchical, violent tendencies of

humans--just as Americans told their enslaved Africans

they were fortunate to be rescued from barbarism by

their "democratic" enslavers.

Like the enslaved people and their

descendants, Lilith and her children feel enormous

ambivalence about her choice. In Adulthood

Rites, Part 2 of the trilogy,

Lilith’s half-Oankali son chooses for a while to live

apart with the human "resisters," those who choose

sterility rather than join the Oankali. He at last

convinces the Oankali to provide a new home for the

resisters, where they can breed again and regenerate the

human species. The home provided is the planet Mars;

reshaped for habitability, to be sure, but all of

humanity is outcast from their own homeland, like Native

Americans forced onto a reservation. Lilith’s son risks

his life to allow humans to choose humanity; yet he

himself returns to his own hybrid heritage among the

Oankali. Throughout Butler’s work, people of various

ethnic and cultural backgrounds struggle to make such

choices.

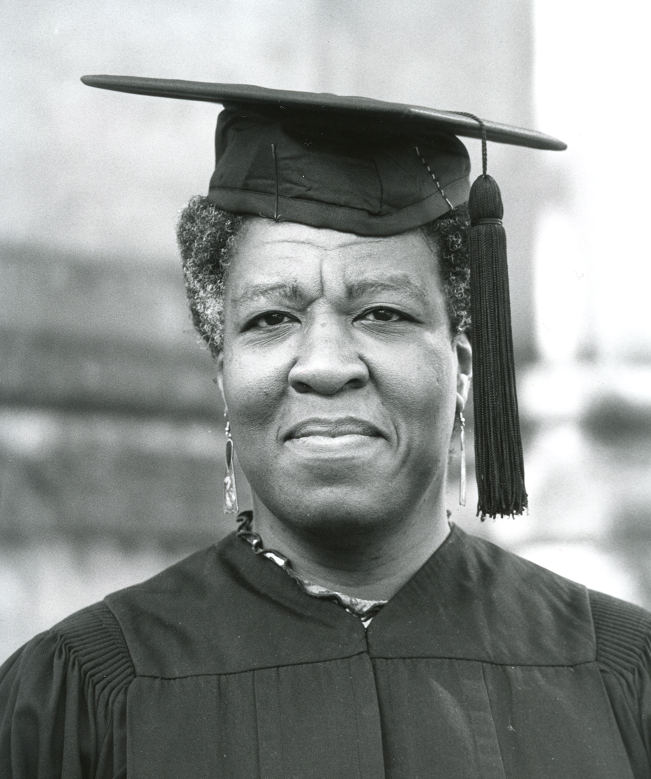

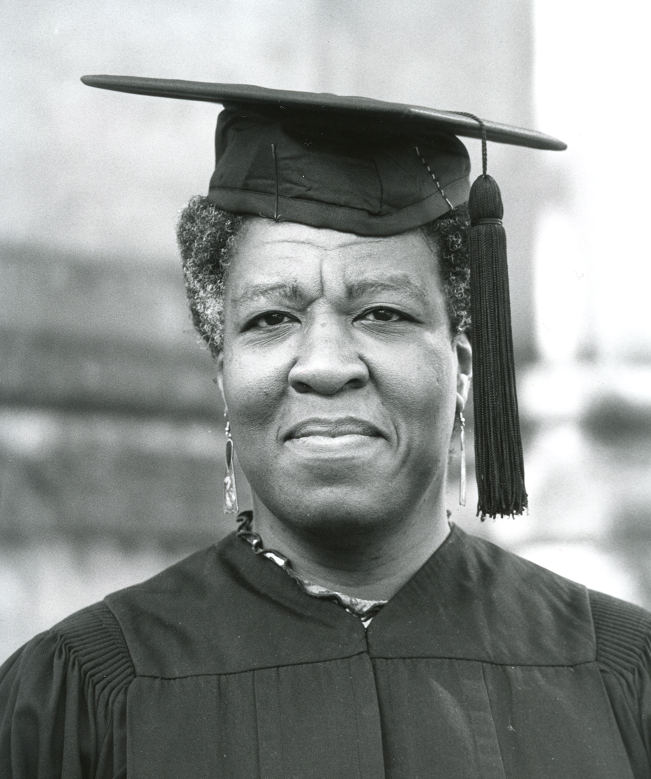

Lilith’s ambivalence about the Oankali, and

about her own genetic heritage, echoes Butler’s own

experience in the community of writers. For many years,

Butler was one of only a few Black female writers of

science fiction. Her gifts were embraced and appreciated

by many fellow writers, and found success with

supportive publishers. Yet for publication, she had to

accept cover illustrations depicting her Black

characters as Caucasian. Butler’s success required

denial of her own racial identity, just as some of the

early women writers of science fiction had to deny their

gender by writing under male pseudonyms. Thus, she

shared Lilith’s dilemma by accepting literary success at

the cost of part of her own identity.

In the Xenogenesis books,

the transformation of humanity is accomplished by alien

biotechnology, performed by genetic engineers called ooloi,

who participate in the mating of human and Oankali.

Until recently, genetic crossing of unrelated animals

was considered untenable from the standpoint of biology.

Yet in the past decade, biologists have discovered

profound sources of genetic commonality between

organisms as distant as humans and fruit flies.

Reproductive technology has led to chimeric combinations

such as sheep and goat; and an early human embryo has

been generated from the egg of a cow. Researchers have

proposed introducing the chimpanzee’s "superior" disease

resistance genes into human chromosomes. Thus, a science

fiction writer can now propose alien interbreeding based

on reasonable biological speculation; but few writers

develop the biological basis as effectively as Butler

does.

How could a species naturally evolve a

lifestyle requiring the acquisition of genes from

unrelated species? In the years since Dawn was

published, research has revealed interesting parallels

to the Oankali in the population dynamics of living

organisms on Earth. Microbes and plants have been shown

to possess surprising capacities for "genetic trade"

with other species, even taking up naked DNA released by

dead organisms and incorporating it into their own

chromosomes. Our current view of bacteria is that, like

the Oankali, these single-celled organisms evolve so as

to keep only the limited set of genes they need for

their current environment, but retain nearly endless

capacity to acquire new genes, such as genes for

antibiotic resistance, from DNA "out there." Similarly,

plants in the natural environment have shown an

unexpected capacity to acquire herbicide resistance

genes from crop plants genetically engineered for

resistance, a discouraging sign for the future of weed

control.

Butler is one of few science fiction writers

to explore the positive potential of "bad" genes.

Genetic variants which seem defective under current

conditions may confer benefits when conditions change;

for example, a rare defect in the structure of white

blood cells confers resistance to HIV infection.

Butler’s Oankali are particularly interested in human

mutations that cause cancer. Cancer results from a

series of mutational "steps" in a few cells of the body,

leading to loss of control of growth. Yet the genes in

which these mutations occur are some of the most

critical genes of the body, vital for normal processes

of growth and development. Furthermore, some of the

viruses which cause cancer-inducing mutations have now

been developed into "vectors" of gene therapy, used to

correct or ameliorate genetic defects in human patients.

Thus, in Butler’s story, it makes sense that the Oankali

consider cancer genes to be some of the most valuable

genes for which they "trade."

From the Oankali embrace of human cancer

genes, Butler draws a broader message, that we humans

need to embrace "otherness" in ethnicities and cultures

foreign to our own, even if at first they seem to

violate our own values. But how far can--or should--our

embrace reach? Butler does not provide easy answers.

Which leads us to the question: Is there a

downside to Butler’s Oankali saviors of humanity? Do the

Oankali really represent a positive solution to the

problem of human "hierarchal tendencies," as implied by

the first book, Dawn? Is

the "non-hierarchal" way of the Oankali an absolute

improvement; or is it at once salvation and the

damnation we self-destructive humans deserve?

The concluding book of the trilogy, Imago, depicts

human-Oankali ooloi as

the ultimate post-colonialists, consummate genetic

engineers who sample the genes of all different

organisms for their "interesting taste," rather as

Americans choose to dine at ethnic restaurants. The fact

that all of Earth’s species will ultimately vanish, as

the Oankali consume the planet, does not disturb them. A

similar genetic consumerism can be seen today as biotech

companies search the dwindling rainforests for rare

species, storing their genes for useful pharmaceuticals

before the organisms vanish. Some research programs even

target indigenous human populations--ethnic groups whose

rare genes might enhance the health of Americans long

after their own races are gone. Such research

understandably draws indignant responses from those

facing extinction.

In fact, the closer one looks, the Oankali are

not our opposites, but rather an extension of some of

humanity’s most extreme tendencies. Humans disturb and

pollute our ecosystem; the Oankali will literally

consume every organic molecule of it. Humans in the

traditional Western Christian view, consider procreation

the sole function of sexuality. The Oankali—despite

Butler’s critical stance toward Christian

religions—basically share this view.

Meanwhile, the Oankali "gene trade," which

seems so fearsome in Dawn, may

be less unthinkable than we suppose. Would middle-class

Americans today ever actually trade away their own

genes, let alone their future children, as Lilith does?

One need only look to the notice boards of Ivy League

colleges, where students are invited to sell their own

eggs to infertile strangers; and many do so, to help pay

their tuition. The recipients who buy the eggs inquire

into the donors’ genetic and personal backgrounds, as

obsessively as the Oankali analyze Lilith. Ironically,

the medical process of induced ovulation jeopardizes the

future fertility of "egg donors," who may someday

require similar services to produce children of their

own. The business of egg banks and sperm banks has

become consumerized, with recipients shopping for

particular traits in pursuit of perfect offspring. The

Oankali, with their alien genetic engineering, have

become hauntingly familiar.

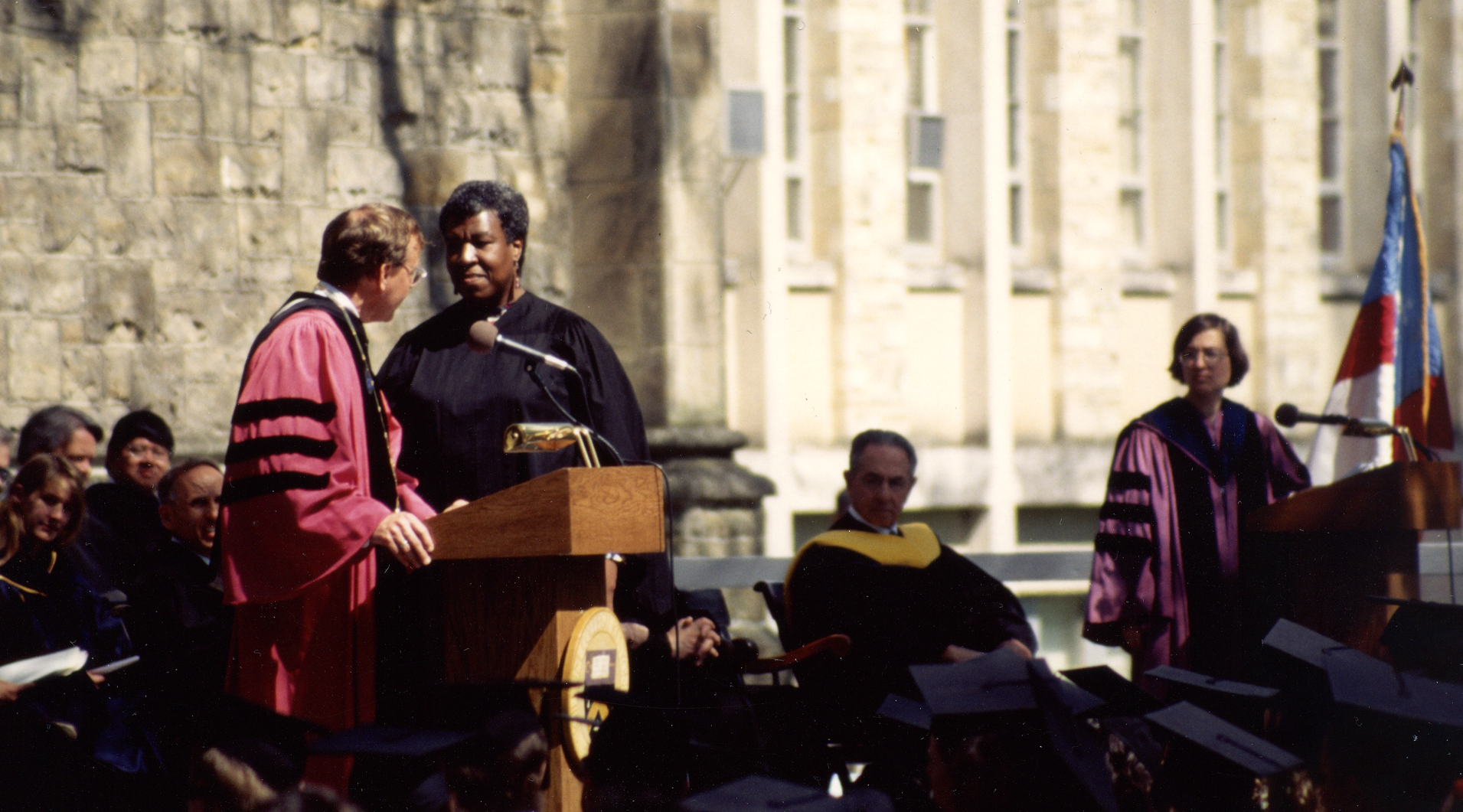

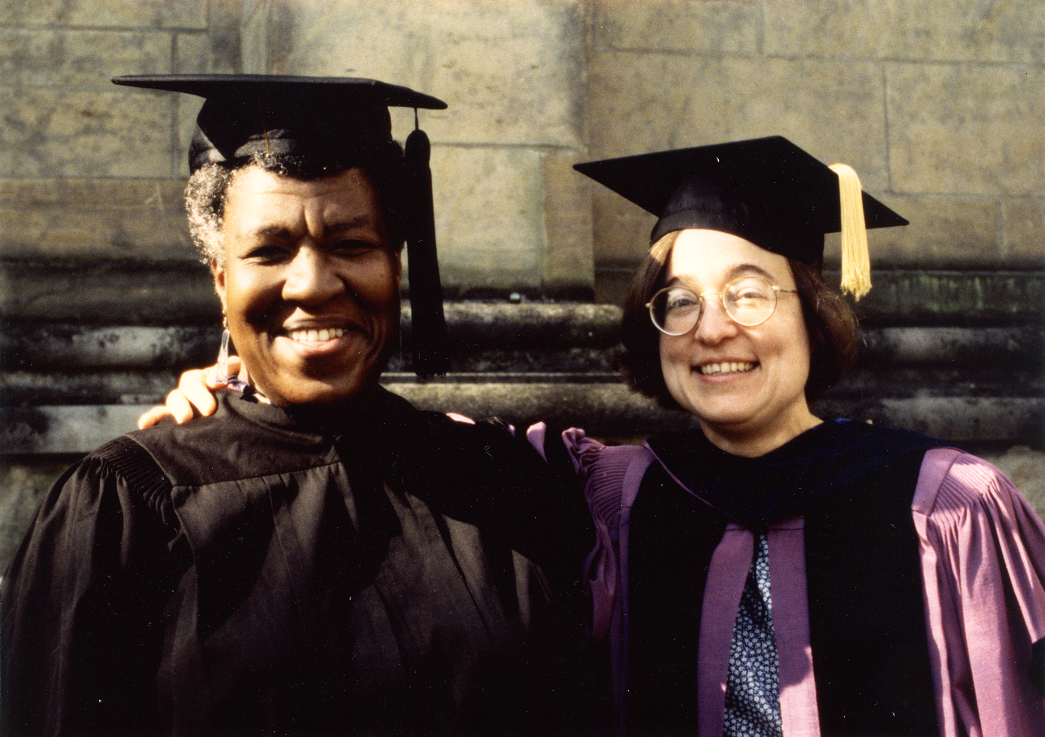

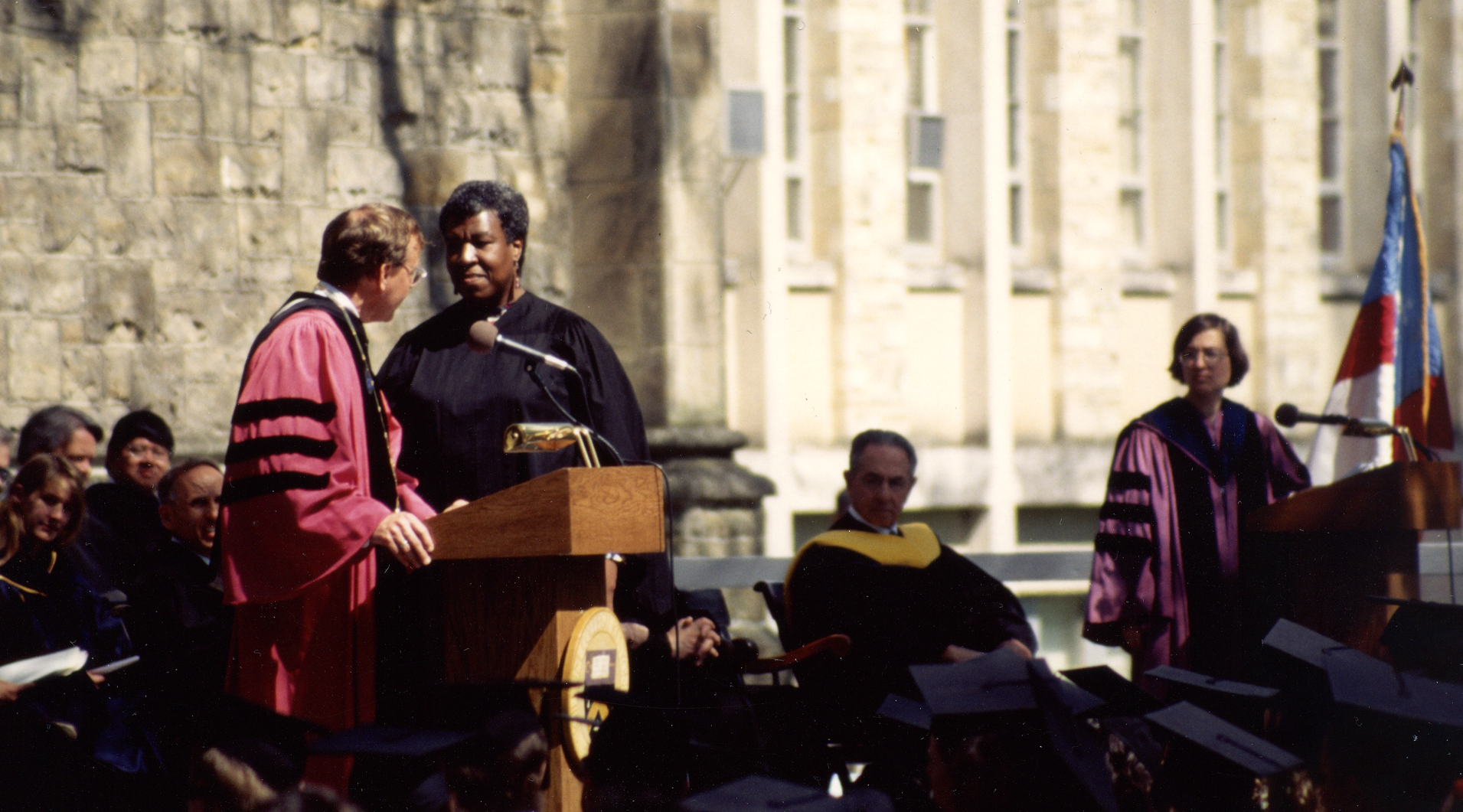

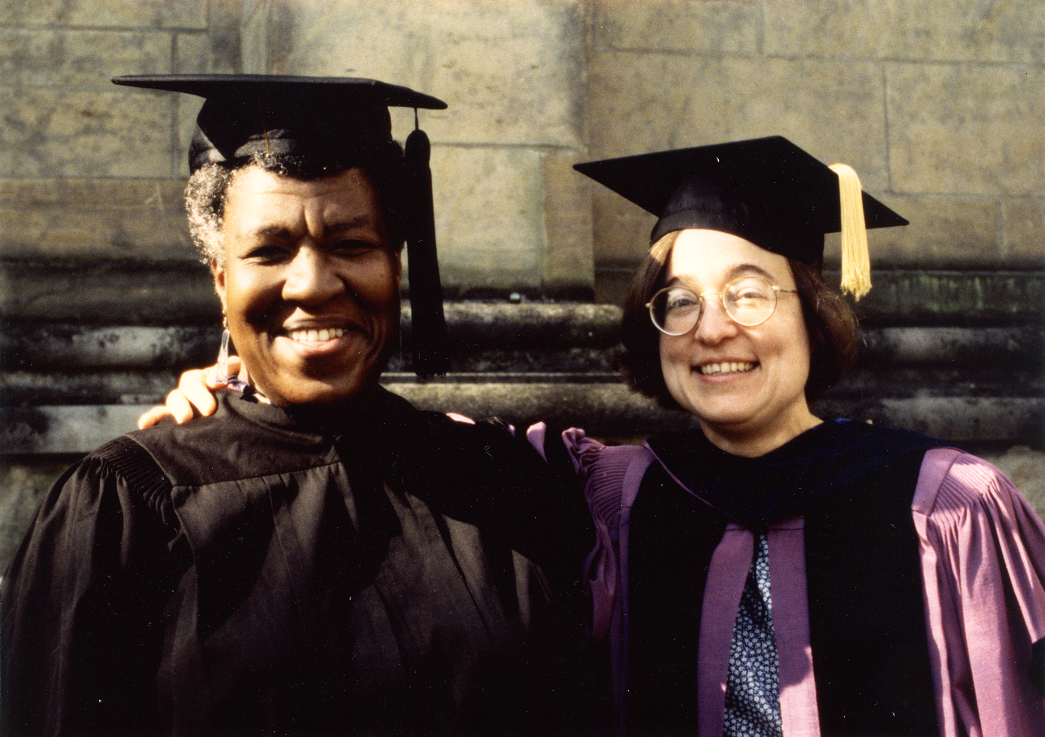

Adapted from Joan Slonczewski's presentation

at the Science Fiction Research Association, Cleveland,

June 30, 2000; published as “Octavia Butler’s

Xenogenesis Trilogy: A Biologist’s Response,” pp

149-155, in Alexandra Pierce and Mimi Mondal, eds. Luminescent

Threads: Connections to Octavia E. Butler. Yokine,

Australia: Twelfth Planet Press, 2017.

Octavia E. Butler’s

predictions in Parable of the Sower

and Parable of the Talents

By Jeanne

Griggs

Octavia E.

Butler’s novel Parable of the Talents, published in 1998

as a sequel to the events in the Parable of the Sower

(1993), describes the election of a president who “insists

on being a throwback to some earlier, ‘simpler’ time. Now

does not suit him. Religious tolerance does not suit him.

He wants to take us all back to some magical time when

everyone believed in the same God, worshipped him in the

same way, and understood that their safety in the universe

depended on completing the same religious rituals and

stomping on anyone who was different” (18). The president

has support for his plan to “make America great again”

(18).

Many of Butler’s other predictions from

these two novels have come true; we’re already living in

her imagined “period of upheaval…from 2015 through 2030”

(PT, 8). As California wildfires, freezing in Texas,

flooding in Missouri and articles about climate change

indicate, we’re already living in a world going through a

period of upheaval. Lauren Olamina, the protagonist of

Parable of the Sower, says that she has “watched as

convenience, profit, and inertia excused greater and more

dangerous environmental degradation.” (PS, 8). And who

living today has not?

Butler paints a picture of how climate

change could affect people in California; people of color,

in particular. Her protagonist knows that “people have

changed the climate of the world” (PS, 50) and she means

to survive instead of “waiting for the old days to come

back.” The president in Lauren Olamina’s world has

suspended “overly restrictive” (PS, 24) environmental

protections, while in the real world our president did the

same. In its last update, the New York Times listed more

than one hundred environmental rules rolled back under the

Trump administration, based on research from Harvard Law

School, Columbia Law School and other sources. The

compilers of the list prefaced it at one point by saying

that “President Trump has made eliminating federal

regulations a priority.”

Water is so scarce for the characters in

The Parable of the Sower that it “costs several times as

much as gasoline.” In their journey north, they have to

plan to travel through places where they can buy water.

They use “commercial water stations” because “anything you

buy from a water peddler on the freeway ought to be

boiled, and still might not be safe. Boiling kills disease

organisms, but may do nothing to get rid of chemical

residue—fuel, pesticide, herbicide, whatever else has been

in the bottles that peddlers use. The fact that most

peddlers can’t read makes the situation worse. They

sometimes poison themselves” (PS, 180). But “commercial

stations let you draw whatever you pay for—and not a drop

more—right out of one of their taps. You drink whatever

the local householders are drinking. It might taste,

smell, or look bad, but you can depend on it not to kill

you” (PS, 181). At one point, Lauren’s group plans to head

for a “big freshwater lake—San Luis Reservoir” pictured on

one of Lauren’s old maps, saying “it might be dry now.

Over the past few years a lot of things had gone dry. But

there will be trees, cool shade, a place to rest and be

comfortable. Perhaps there will at least be a water

station” (PS, 222). When they arrive, they find that

“there is still a little water in the San Luis Reservoir.

It’s more fresh water than I’ve ever seen in one place,

but by the vast size of the reservoir, I can see that it’s

only a little compared to what should be there—what used

to be there” (231). We can say the same about Lake Mead in

2022. Lest we believe that less arid states will fare

better, Lauren mentions that “there’s cholera spreading in

southern Mississippi and Louisiana….There are too many

poor people—illiterate, jobless, homeless, without decent

sanitation or clean water. They have plenty of water down

there, but a lot of it is polluted.”

Belief in change helps prepare Lauren to

survive, as she sees that those who look to the past—to

some possibility of living the way we used to, before

climate change--perish. If we focus only on trying to

repair or delay the damage we’ve already done to our

planet, we’re trying to live in the past—an example of

this is Lauren’s sustainable farming community, Acorn,

which is taken over by “Crusaders” who won’t return their

children until they accept the president as “God’s chosen

restorer of America’s greatness” (PT, 201).

Butler’s Parable of the Sower and Parable

of the Talents show the importance of learning to accept

change enough to work towards it, to turn our minds

towards imagining a future for our planet.

Adapted from Jeanne Griggs'

presentation at the International Conference for the

Fantastic in the Arts, Orlando, March 2021.

|