Pack

movements and territories

A wolf pack may be territorial or migratory (Chapman,

1978). Mech (1973 cited in Mladenoff, 1995) in part defines wolf packs as subpopulation

units that occupy consistent territories. The range of a traveling wolf pack

depends on the individual wolves, the season, the nature of the country, and

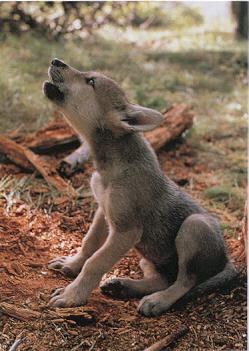

the availability of prey, among multiple other factors. In the spring, a lone

male and a lone female find each other, mate, and produce pups in a den (Rothman

and Mech, 1979 cited in Mech et al., 1998). Pack movements are centered around

the den, but the adults radiate out to hunt and bring back food to the pups.

Usually after a couple of months the pups leave the den and live above ground

at rendezvous sites (Schullery, 1996). Starting in the fall the pups are grown

enough to travel with the adults and the pack moves through its territory.

The

pack's movement is outlined as two seasonal phases, den-based summer movement

and nomadic winter movement (Mech et al., 1998). Therefore it is essential that

there exist great areas of wild, mountain land for packs to travel and establish

their own territories. Mech (1998) claims "wolves and long travel are almost

synonymous." Wolf pack territories in Minnesota range from 25 square miles to

150 square miles, and in Alaska and Canada territories may be 200 to 1,000 square

miles. The natural tendencies of wolves traveling through grand spaces is very

important as packs are reintroduced to areas with infiltrating human impacts

and increasing land fragmentation.

The

pack's movement is outlined as two seasonal phases, den-based summer movement

and nomadic winter movement (Mech et al., 1998). Therefore it is essential that

there exist great areas of wild, mountain land for packs to travel and establish

their own territories. Mech (1998) claims "wolves and long travel are almost

synonymous." Wolf pack territories in Minnesota range from 25 square miles to

150 square miles, and in Alaska and Canada territories may be 200 to 1,000 square

miles. The natural tendencies of wolves traveling through grand spaces is very

important as packs are reintroduced to areas with infiltrating human impacts

and increasing land fragmentation.

next to Patterns

and trends in dispersal

return to Social

Structure & Dispersal

return home

The

pack's movement is outlined as two seasonal phases, den-based summer movement

and nomadic winter movement (Mech et al., 1998). Therefore it is essential that

there exist great areas of wild, mountain land for packs to travel and establish

their own territories. Mech (1998) claims "wolves and long travel are almost

synonymous." Wolf pack territories in Minnesota range from 25 square miles to

150 square miles, and in Alaska and Canada territories may be 200 to 1,000 square

miles. The natural tendencies of wolves traveling through grand spaces is very

important as packs are reintroduced to areas with infiltrating human impacts

and increasing land fragmentation.

The

pack's movement is outlined as two seasonal phases, den-based summer movement

and nomadic winter movement (Mech et al., 1998). Therefore it is essential that

there exist great areas of wild, mountain land for packs to travel and establish

their own territories. Mech (1998) claims "wolves and long travel are almost

synonymous." Wolf pack territories in Minnesota range from 25 square miles to

150 square miles, and in Alaska and Canada territories may be 200 to 1,000 square

miles. The natural tendencies of wolves traveling through grand spaces is very

important as packs are reintroduced to areas with infiltrating human impacts

and increasing land fragmentation.